The Safe Light Regional Vehicle (SLRV) is notable for its exceptionally lightweight yet very safe body, built using a sandwich construction.

With a range of around 400 kilometres based on compact electrical transmission powered by a fuel cell, the SLRV should serve primarily as a car for commuters and those travelling from A to B. For instance, getting from the outskirts into the city centre or travelling about in the area around the city – in other words, anywhere that local public transport does not offer comprehensive coverage.

Sandwich design: lightweight, safe and cost-effective

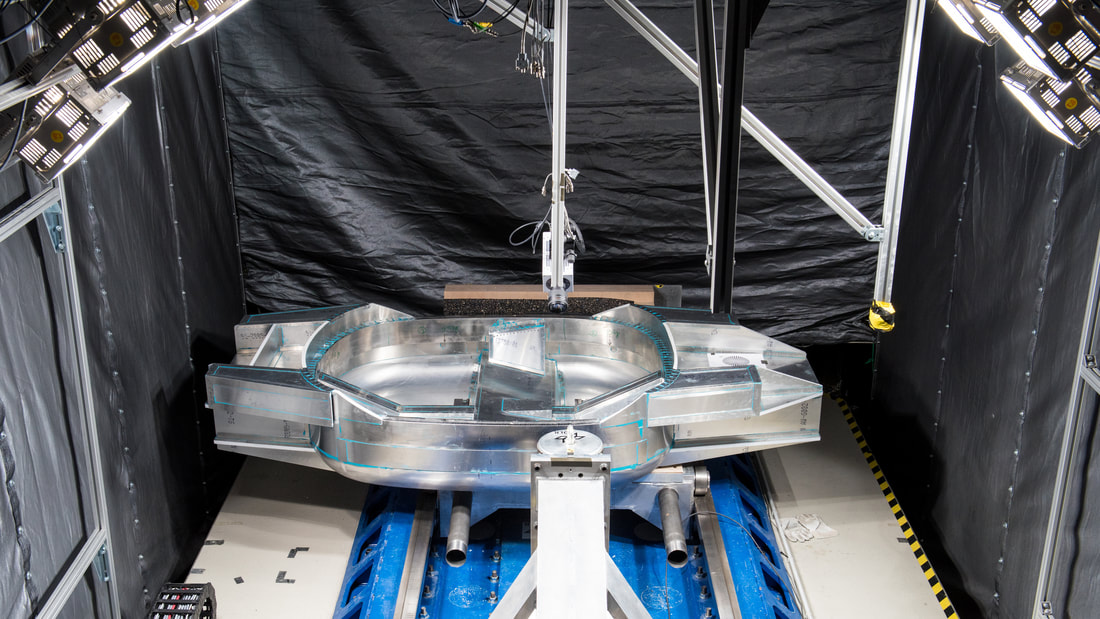

The body of the two-seater SLRV is low and elongated in order to ensure as little aerodynamic resistance as possible. Weighing only around 80 kilograms, it is remarkably light, yet very safe and inexpensive to produce. This is possible thanks to the sandwich construction method. The sandwich material used comprises a metal top layer and a plastic foam interior. The front and rear parts of the SLRV are made of sandwich panels and serve as crash zones. These sections also house much of the vehicle technology. The passenger space consists of a shelll with an attached ring structure. This absorbs the forces that act on the car while driving and should protect the occupants in the event of a crash.

The body of the two-seater SLRV is low and elongated in order to ensure as little aerodynamic resistance as possible. Weighing only around 80 kilograms, it is remarkably light, yet very safe and inexpensive to produce. This is possible thanks to the sandwich construction method. The sandwich material used comprises a metal top layer and a plastic foam interior. The front and rear parts of the SLRV are made of sandwich panels and serve as crash zones. These sections also house much of the vehicle technology. The passenger space consists of a shelll with an attached ring structure. This absorbs the forces that act on the car while driving and should protect the occupants in the event of a crash.

Put to the test: the car body during frontal and pole crashes

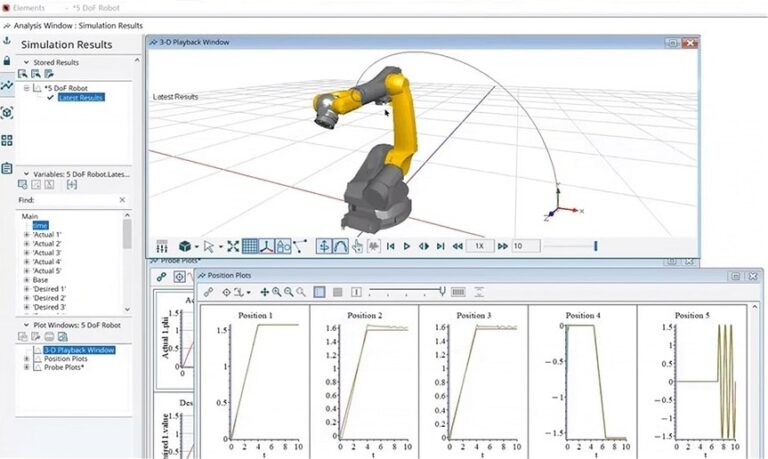

Kriescher’s team has spent many hours on the computer constructing the body of the SLRV and simulating different load scenarios. With a view to testing their calculations, the scientists have also built two prototypes and tested them at DLR’s own crash-test facility at the Institute of Vehicle Concepts in Stuttgart. “We conducted a frontal and a pole crash similar to those performed by the car industry. The pole crash is particularly hard on any kind of car body, as it simulates the side impact of a car when it strikes a hard object, like a tree,” Kriescher says. For this crash, the researchers screwed the SLRV body onto a fixed carriage. The obstacle, in this case a pole-like impactor, was mounted on a mobile carriage. Over a few metres, a catapult accelerated this carriage to a speed of almost 30 kilometres per hour and launched it into the car body. Several high-speed cameras recorded both experiments from different angles. Using measuring points that they had previously stuck to the body, the DLR researchers were then able to examine the movement and deformation at individual points with precision.

Kriescher’s team has spent many hours on the computer constructing the body of the SLRV and simulating different load scenarios. With a view to testing their calculations, the scientists have also built two prototypes and tested them at DLR’s own crash-test facility at the Institute of Vehicle Concepts in Stuttgart. “We conducted a frontal and a pole crash similar to those performed by the car industry. The pole crash is particularly hard on any kind of car body, as it simulates the side impact of a car when it strikes a hard object, like a tree,” Kriescher says. For this crash, the researchers screwed the SLRV body onto a fixed carriage. The obstacle, in this case a pole-like impactor, was mounted on a mobile carriage. Over a few metres, a catapult accelerated this carriage to a speed of almost 30 kilometres per hour and launched it into the car body. Several high-speed cameras recorded both experiments from different angles. Using measuring points that they had previously stuck to the body, the DLR researchers were then able to examine the movement and deformation at individual points with precision.